The Simplex method ... in real life!

Optimizing simply on big data using either your own version of Simplex or SciPy's linear optimization algorithm

Introduction

Ever since I started to learn more math than most adults around me could remember, I began looking (mostly unconsciously) for the ways the things I was learning could apply to my life. Turns out, I’m still learning, and it’s still just as fun. Today I want to share with you about an important principle of finding the best solution for a problem, what people like me call optimization.

Optimization

Optimization is simply finding an “optimal” solution - the best for what you have. We humans optimize all the time - finding the quickest way to get somewhere (although we’ve given this task to computers), picking the best thing to order at a restaurant, or the right words to say when trying to express your love to someone. Sometimes our brains are really good at this, and sometimes they aren’t. In many situations, an “optimal” solution (the very best possible) isn’t worth the time or effort, since you can probably come up with a pretty good solution with a lot less thinking. In deciding not to put in that effort, you actually just optimized how you use your time! Pretty cool.

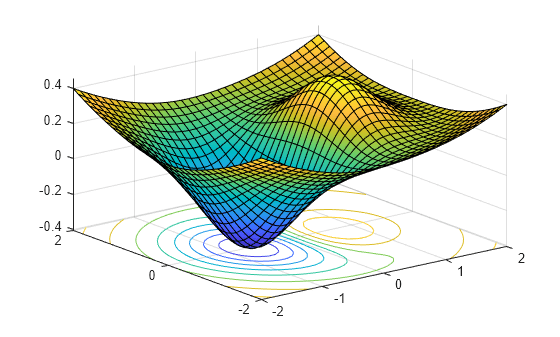

When we do need to optimize, we can use mathematics to put together a function (often called a loss or objective function) where our inputs are all the things we can decide (or “tweak”) and our output is how much “good” or “bad” we get out of it. Finding the optimal point is often visualized as finding a peak or a valley in the graph of this function.

In business and academic pursuits, it can totally be worth it to find an optimal or near-optimal solution, especially when there is too much data for any brain to process. Take this example:

Real-Life Example: Optimization in Lead Generation

Over the summer I had the opportunity to work as a data scientist for a company that supports a team of 400+ salespeople. A big part of sales are what we call “leads” - the people who are more likely to buy the thing you sell and less likely to get annoyed that you’re trying to sell to them. Obtaining these leads can be difficult and expensive. This was my process to be able to find the “optimal” lead purchasing/generation strategy:

- Analysis: Through some good data science digging we discovered that some things, like which vendor we bought the lead from (the vendor that led each person to us), affected how likely this person was to buy our product. In simpler terms, people from some vendors were generally more interested than from others.

- Model building: This difference in interest, which we measured by % of sales per lead, was correlated with a number of different pieces of information about the leads. Leads also varied in cost depending on these pieces of information. I needed to talk to lots of people at the company to understand how all this information came together to affect company processes, expenses and profits.

- Big data optimization: All this information comprised tens of thousands of pieces of data, which isn’t so much for a computer but quite a bit for any brain in the office! With the help of Python (described below), I was able to find an “optimal” solution for how, when, and where we should buy leads, to maximize total profit with respect to all the limits we had as a company.

Linear Optimization

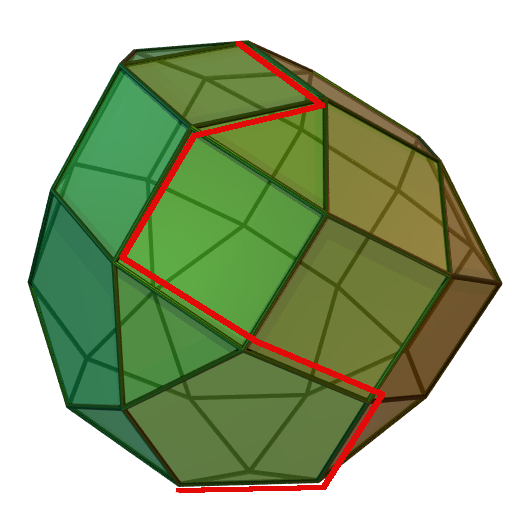

In this example, I employed a specific type of optimization called linear optimization, also known as linear programming. If general optimization is like finding the lowest point in a valley, linear optimization with linear constraints is like finding the lowest point in a soccer ball with lots of flat sides.Linear optimization is easier to solve than most other forms of (nonlinear) optimization, because the function to find the best thing (objective or loss function) is linear (a straight line). If changing one thing makes the solution better, than changing it more like that will just make the solution even better. The caveat is that eventually you will probably run into some constraint, like in the case of our leads and sales, not having enough salespeople to call the leads back.

The Simplex method

Linear optimization can be solved so quickly due to an algorithm called the Simplex method. Let’s go back to the idea of the soccer ball (and remember, normally the computer has to deal with a soccer ball in n-dimensional space where n is a lot bigger than 2). To find the lowest point on a soccer ball, we actually know that it has to be at one of the corners (or vertices), so we can start at any vertex and just walk around the edges, getting lower and lower until we come to the bottom.

The algorithm is mathematically simple enough that I have done it by hand and coded it in Python. A portion of my code is shown below, and the full result is pushed here.

def solve(self):

"""Solve the linear optimization problem.

Returns:

(float) The minimum value of the objective function.

(dict): The basic variables and their values.

(dict): The nonbasic variables and their values.

"""

# keep pivoting when there is a negative coefficient on the top row

while not np.alltrue(self.D[0, 1:]>=0):

self.pivot()

min_obj = self.D[0,0]

basic = dict()

nonbasic = dict()

# add results to dictionaries

for i in range(self.n+self.m):

i1 = i + 1

e = self.D[0, i1]

if e==0:

r = np.argmin(self.D[:, i1])

basic[i] = self.D[r, 0]

elif e>0:

nonbasic[i] = 0

return min_obj, basic, nonbasic

Feel free to learn how to code the simplex algorithm just like I did with this great lab resource, written by my BYU professor Tyler Jarvis and others.

The wonders of SciPy

Thankfully someone coded this and other algorithms better than I did, and it is available in an open source library called SciPy. Specifically, it can be implemented using a method called linprog in SciPy’s optimize package. This is what I used to find my linear solution for lead generation.

Conclusion

This tutorial was likely insufficient to teach the in depth features of what the Simplex method does, or how to use SciPy’s optimize.linprog method, so if you’re interested in implementing linear optimization into your work, I would recommend diving deeper into understanding the linear constraints and objective function. I hope you enjoy optimization as much as I do, and I challenge you to not only try optimization in Python but also in your daily life - breaking down decisions into logical pieces can sometimes be very useful.